If you venture outdoors this summer, there is a good chance that you, like 500,000 other Americans, will return home with a friend. Her name is Ivy. Her victims call her Poison.

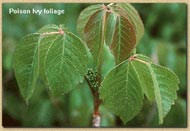

Each year, that is the number of people who develop what is technically called contact dermatitis. It is the result of coming in contact with the toxic agent present in a trio of plants called poison ivy, poison sumac and poison oak. Though each is a different family, all have one thing in common. They contain an oily substance called urushiol (pronounced oo-roo-shee-ohl) that flows with the sap of the plant. Urushiol is one of the most toxic substances on the planet. It won’t kill you, but as little as one-billionth of a gram can cause a skin reaction. So if you are out anywhere near plants and brush up against one of the three cousins and get a little of the sap on you, you can expect to see a reaction within hours. A red, linear rash, accompanied by extreme itching or burning will let you know your new friend has arrived. She’ll be hanging out for two or three weeks and you’ll be giving her lots of attention until she leaves.

The rash that comes with exposure to poison ivy, oak or sumac is actually an allergic reaction. A few people and most all animals are unaffected by the toxin, but 85 percent of all humans will get to know the real meaning of itch. Sometimes a first exposure brings no reaction and if it does, it may take a week to show up. But successive contact increases the likelihood of a rash developing. For some reason though, as a person ages the sensitivity diminishes. Old people don’t get poison ivy. But maybe they just don’t go into the woods.

Don’t touch me there

Although the three plants are all related as members of the cashew family, not all are found throughout the United States. Hawaii and Alaska are free  of the three. Poison sumac is mostly found east of the Mississippi River and in the Southeast. Poison ivy is rarely found west of the Rocky Mountains. That is poison oak country. There is neither poison ivy nor poison sumac in California, only poison oak. Usually none of the three can be expected above 5000 foot elevations. of the three. Poison sumac is mostly found east of the Mississippi River and in the Southeast. Poison ivy is rarely found west of the Rocky Mountains. That is poison oak country. There is neither poison ivy nor poison sumac in California, only poison oak. Usually none of the three can be expected above 5000 foot elevations.

The plants are hardy and can grow almost anywhere. They like water and ravines and are easy to miss among the more harmless vegetation. Still, the best way to avoid getting a dose of dermatitis is to avoid the plant and its toxic oil.

You can save your rash

The plants contains urushiol no matter the season. In fact, dead plants can be as bad as live ones. When a person comes in contact with poison ivy, it’s the urushiol oil that is the problem. Since it is an oily liquid, it can get on tools, gloves, clothing or pets and then be transferred to the skin. The oil can remain toxic for years. In a matter of minutes or hours after contact, depending on conditions, the toxin penetrates the skin and the rash is inevitable. Some experts say you have a period of time to wash the contact area thoroughly and avoid the rash. Be sure to use a solvent type soap, not an oil-based one, or the oil will just be spread. If in doubt, just use plenty of clean, cool water. Hot water will spread the oil.

But there is another remedy. Nature provides, as they say, and in the case of poison ivy that holds true. The moment you make the mistake of contacting some poison ivy, you won’t have to look far for the cure. There is a plant that almost always grows right near poison ivy that will save you the redness, swelling, rash and itching poison ivy promises. The answer is in the herbal plant known as jewelweed.

Jewelweed is the common name for a member of the impatiens family. It is also called the spotted touch-me-not. It is so named because the leaves tend to bead up the morning dew to the appearance of tiny jewels. Favoring the same growing conditions as poison ivy, jewelweed is found throughout North America growing right next to the problem.

If you contact poison ivy, look for some jewelweed nearby. You can find it by its purple-spotted orange flowers about an inch long. Crush up some of the stems and leaves and rub on the site of contact. The jewelweed will keep the rash from developing or at least minimize the effect. It is likely that time is an important factor; the sooner, the better.

A researcher at Rutgers University, Dr. Robert Rosen, believes that a chemical in jewelweed called lawsone binds with the molecular location that urushiol attacks in the skin cells. If lawsone gets there, urushiol has no effect and no rash develops. Based on that idea, it seems that jewelweed might be a good prophylactic measure too. Rubbing some on before hiking might work.

After a reaction has already set in and the rash appears, there are still some things you can do to make it bearable. Jewelweed can soothe the rash after it appears. A paste of baking soda and oatmeal can lessen the itch. Another useful herbal is the buckthorn plant. Also known as plantain, the leaves have a thick, green sap that supposedly soothes the itch for up to 24 hours. The New England Journal of Medicine even recognizes that one. The old standby skin care herb, aloe vera, is often mentioned as a soothing balm. Even a cool bath with corn starch in the water can help. Unfortunately, only time (about two weeks) will make the blisters and rash go away. Scratching won't cause the rash to spread but it doesn't help it heal.

Some sources advise against antihistamines for the itch because of the problems the drugs cause. On very rare occasions, exposure on the face can cause swelling so extreme that medical attention is required to make sure breathing is possible.

If you’re faced with clearing a stand of poison ivy, use common sense in handling it now that you realize it’s the oil that is the problem. Don’t touch your skin with gloves or tools, wash everything thoroughly afterwards, and never, ever burn poison ivy. The smoke will carry the oil into your lungs and you will get the rash there. That could guarantee a hospital visit.

Be well.

|

of the three. Poison sumac is mostly found east of the Mississippi River and in the Southeast. Poison ivy is rarely found west of the Rocky Mountains. That is poison oak country. There is neither poison ivy nor poison sumac in California, only poison oak. Usually none of the three can be expected above 5000 foot elevations.

of the three. Poison sumac is mostly found east of the Mississippi River and in the Southeast. Poison ivy is rarely found west of the Rocky Mountains. That is poison oak country. There is neither poison ivy nor poison sumac in California, only poison oak. Usually none of the three can be expected above 5000 foot elevations.